Last post, I tried to tackle the goodness of God as one of two assumptions for the basis of my argument in favor of a relational plurality within the unity of God. Today I would like to address the other assumption: that human beings are made in the image of God.

This is perhaps more difficult without relying upon revelatory sources for drawing such a conclusion. I do believe, however, that there are three naturally discernible universalities which strongly infer that human beings are creatures who bear the imprint of the Divine nature in a representational manner.

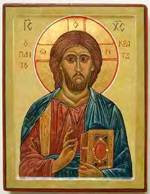

First, human beings have with some variation affirmed anthropic characteristics in the divinities they have worshiped. In both polytheistic and monotheistic influenced cultures, we find deities which to various degrees take on human form, engage in human types of interaction, and are interacted with in an analogous way as one would with another human being (and vice versa is claimed as well). Whether, an ancient Hebrew invokes the curse of a "jealous" God upon his enemies, or a Hindu bows before a very human looking icon of Shiva; whether, an Aztec craftsman creates a grotesque relief of a deity with an animal's head upon a human body, or a neo-pagan in Iceland calls upon Thor--a god who can die just like any mortal person--we see an innate drive to identify humanity and divinity very closely.

Can this simply be a human tendency to anthropomorphize? It could, were this an isolated feature and no other dynamics were at work. However, there are at least two more tendencies to consider.

Second, there seems to be an unabated desire in human beings to connect with "the other" or "the holy." Typically, this manifests itself as prayer or worship or meditation. Somehow, human beings are driven to make genuine contact with something greater than oneself. Even in atheistic or nontheistic worldviews, there is a constant search for enlightenment and a pursuit of wonders which are in some respect greater than human capacities and understanding. There is an innate sense in humans that there must be something more and greater than what is seen or experienced, and we want to become intimate in some way with this "other" thing. St. Augustine would likely classify it as a God-shaped hole in the human heart, but whether one accepts this classification, one cannot escape the universality of this desire.

This desire, being universal, indicates it is part of the creative purpose of God. God wanted human beings to reach out beyond themselves. God created us to do that very thing. This does not ensure we are successful at it, nor does it preclude other desires from interfering with or superseding our longing for God. We can misinterpret what the desire is, or suppress it. But it is there nonetheless.

Since we have this desire from God to be in contact with him, it should help us realize that God desires some sort of communion with us. However, God can only have genuine communion with something like himself. Because we a still creatures and God is the creator, we cannot in our creatureliness alone truly be able to interact with God. In fact, we likely would not have such a desire for contact with God, or "the holy," or enlightenment if we were simply of the same nature as other creatures. A dog may desire to be with her human master, but there is a similarity in our creaturely status shared with the dog that spurs in the dog her desire. Therefore, humanity must possess something of the nature of God within it. Otherwise, we would not have the desire we have.

Third, human beings are moral creatures. C.S. Lewis refers to the shared sense of morals and ethics across cultures as the "tao." Roman Catholics would regard this as natural theology. Some have attempted to disparage any innate morality in humanity, making it simply an evolutionary or cultural construct. But we cannot get away from the fact that humans still beleive some things are right and some things are wrong when it comes to behavior. Murder may be defined more narrowly by a group of cannibals than a Western lawyer, but no cannibal would ever eat anyone from his own tribe. Adultery, even though it has been taken lightly in modern America, still hurts. Children are expected to listen and learn from their parents in every society. We cannot escape such moral strictures. They serve as absolutes to keep us from veering into destructive patterns of behavior.

The universality of moral desire, of the desire for palpable intercourse with the other, and the manner in which divinity has manifested itself in anthropic ways serve as strong signs that we are in some way like God. Humanity must bear a likeness to God, especially in ways which are universal. We can infer such from these natural occurrences, but likely would not have done so without the aid of revelation. Many, perhaps most, human beings do not necessarily come to the conclusion that they are like God in some way without being taught via a claimed revelatory text. Yet, these three arguably primal universal behaviors in humanity suggest the distinct possibility of our being created in God's image. And it is just such a God, one who would make me like him enough to interact with me, that draws from me both thanks and adoration.

8/01/2007

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)