The news is always consumed with conflict--Iraq, Georgia, Afghanistan, the Anglican Communion, the ramp-up to the November election. Where is God to be found in this? Marcion was a heretic who denied a loving God could stomach much less instigate conflict. Yet we are remiss in our biblical and theological understanding if we do not look to reconcile the "war" imagery of ancient Israel with the "peace" imagery made known in Jesus Christ.

First, it is incorrect to find the opposite of peace in violence. The opposite of peace is anarchy, or theologically, the absence of God's rule. Violence is a tool. Some things need to be destroyed, swept away, overcome. I take antibiotics to destroy infection-causing bacteria. I sweep my house and use various cleaners to stem the build-up of dust and debris that would make my home a haven for insects and vermin. The difficulty arises when fallen human beings make use of so dangerous a tool as violence. Which is why we must never use words carelessly or take actions indiscriminately. I am not God, but I seek his direction to know when violence is needed, and know when violence is never justified.

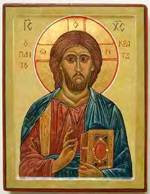

Second, peace can only ultimately be accomplished by God himself. As much as I pray to be an instrument of peace, and as much as I pray for God's kingdom to come on earth, I know that what I can accomplish is limited. All is dependent on the Holy Spirit's carrying out of the salvation made real through Jesus Christ according to the will of the Father.

Third, God never backs down from a fight, but he doesn't always use violence to achieve peace. The ultimate example of this is Christ's self-abasement and sacrifice. Christ is the perfect model of restraint, but Christ's insistence to us to "turn the other cheek" is accomplished by Christ himself. That means it becomes more difficult to discern God's will in a given situation. Perhaps, pacifists are correct as a general rule of thumb, but as Dietrich Bonhoeffer discovered, there are circumstances that demand violent action to bring peace.

Fourth, understand that conflict is not eternal. As ubiquitous as fights are, as longstanding some hatreds carry on over the generations, they all must end. El Salvador, once ripped with sectarian violence, has former enemies celebrating the weddings of their children with one another. They basically, as a nation, just stopped killing. People eventually tire of fighting, and creative solutions to conflict that mirror God's heavenly rule emerge. Is this common grace? Does this point to perhaps a sacramental pain made accessible by violence that causes us to strive for peace? Is the violence that was experienced, as tragic as it is, the necessary precursor in some instances of a cleansing by blood of people's hearts--not in terms of vengeance, but to make them ready to accept peace?

I am still remain unconvinced of pacifism, though for me there is an attraction to the kind of logical consistency it carries. But life, as I've seen it, is a dirty, unpredictable business. And while I believe there are underlying foundations and principles that must guide our approach to conflict, originating in God, the fall-out of sin makes for a much less identifiably consistent outcome and means of approach.

So practically, I see how violence, as a neutral creation, can be used for good ends or ill. I also look to see how God might be using all means redemptively in the midst of conflict. In humility and prayer, I do what I can as best as I perceive it to minimize and squelch the conflict. Finally, I remember that conflict is temporary, and the longer I keep it on life-support, by action OR inaction, the worse it typically is for everyone involved. It's a less-than-perfect ethic for a less-than-perfect world, but I trust that God will forgive my shortcomings as I continue to seek him and live according to love.

8/20/2008

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)